Public interest litigation vs. election petition: The fundamental Rights suffered?

A PIL in the Gujarat High Court questions the absence of a

09-05-2024A PIL in the Gujarat High Court questions the absence of a

09-05-2024The third phase of the 2024 General Elections was held across eleven States earlier this week. As per the press release by the Election Commission of India, polling in the third phase recorded an approximate turnout of 64.4%. The sovereign authority holder i.e. the voters in the States from Assam in the East to Gujarat in the West and from Karnataka in the South to Uttar Pradesh in the North exercised their right to vote.

Out of 26 parliamentary constituencies in Gujarat, elections were held only in 25 constituencies. Candidate from the parliamentary constituency of Surat was declared as “being elected unopposed” by the Election Commission of India. On 22 April, 2024, the Election Commission of India (ECI) gave the ‘Certificate of Election’ to the sole remaining candidate from the parliamentary constituency of Surat. Such a certificate was issued after the nomination forms of some of the candidates were rejected, and after some other candidates withdrew their candidature. On 30 April, 2024, a voter from the parliamentary constituency of Surat presented a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) before the High Court of Gujarat for urgent hearing. It was mentioned that if the matter is not offered an urgent hearing, the petition would become infructuous.

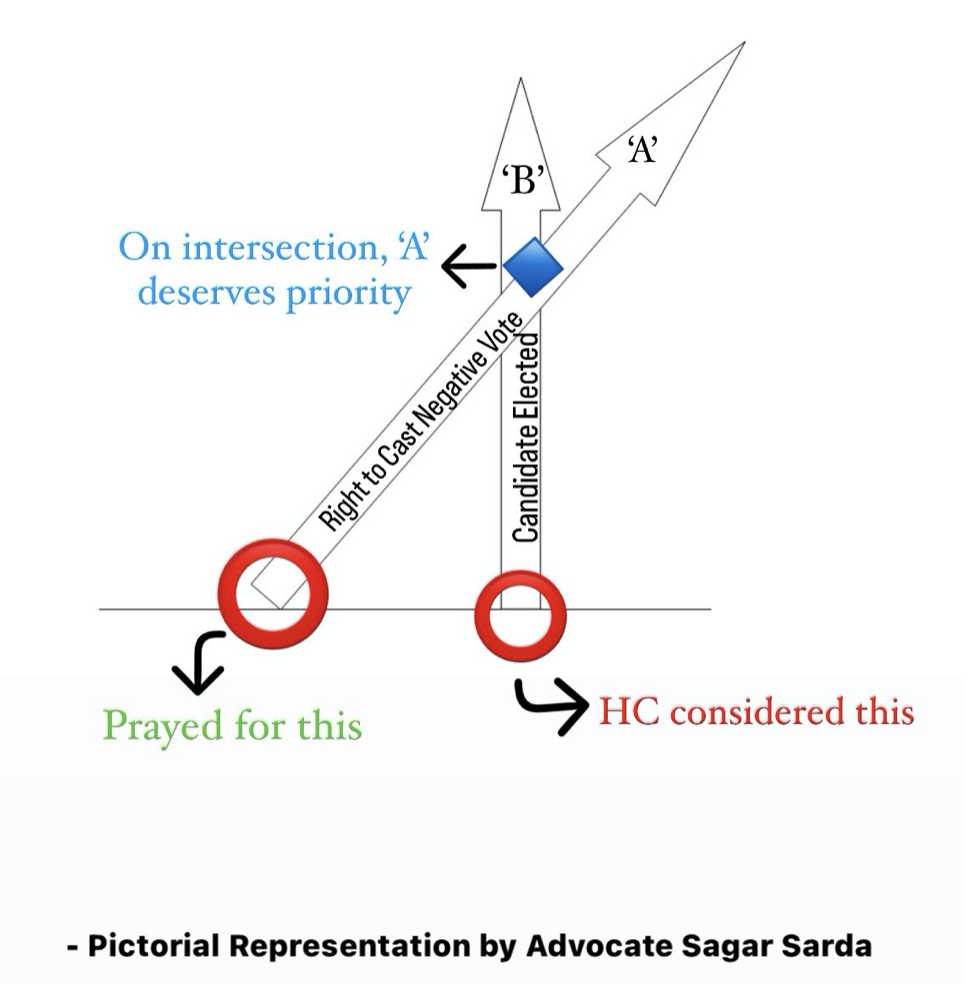

The High Court pointed out that an “Election Petition” challenging the election should have been filed, and not the PIL. The Court remarked that any dispute with regard to election of any candidate on whatsoever ground has to come through an Election Petition only. Therefore, the High Court declined the request of hearing the matter on urgency and opined that a “wrong forum” has been approached by the petitioner. Being the Counsel in the impugned PIL, I defend the arguments made in the Petition, and answer the queries of the Court in chronological order.

In catena of judgments, the Supreme Court has clarified that the right to vote is neither a fundamental right nor a constitutional right, but a statutory right. At the same time, casting of vote by going to the polling both is a significant facet of right to expression of an individual. If this right is denied, it would tantamount to violation of fundamental right under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India. A combined reading of 2002, 2003 and 2006 judgment of the Supreme Court in the cases of Union of India vs. Association for Democratic Reforms, (2002) 5 SCC 294, PUCL & Anr. v. Union of India & Anr., (2003) 4 SCC 399 and Kuldip Nayar v. Union of India, (2006) 77 SCC 1 substantiates the proposition. Since the petitioner claimed violation of the statutory right to vote and the fundamental right to express by way of voting available to the voters in the parliamentary constituency of Surat, High Court is the most appropriate forum to be approached. The Constitution of India empowers the High Court to issue directions, orders, writs in exercise of its jurisdiction under Article 226 for the enforcement of Fundamental Rights and for any other purpose. Therefore, the Writ Petition by way of PIL under Article 226 of the Constitution of India is the foremost forum for any person whose rights, including those guaranteed by Part III, are infringed.

Secondly, the “Election Petition” as suggested by the High Court is fallible on the ground that the petitioner did not challenge the election of any candidate. According to Section 81 of the Representation of People Act, 1951, an Election Petition can be presented only after the election of the candidate, and not earlier. Also, grounds for calling in question the election of such a returning candidate are stipulated under Sections 100 and 101. However, the petitioner did not took support of any such ground, and did not challenge the election of the sole remaining candidate who was given the “Certificate of Election”. The petitioner only averred that the voters of the Surat parliamentary constituency were left bereft of their right to caste a “negative vote”.

In the landmark judgment of People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) & Anr. vs. Union of India & Anr., (2013) 10 SCC 1, the Supreme Court had directed the ECI to insert an option of “None Of The Above” (NOTA) in the Electronic Voting Machine (EVM) so that a positive “right not to vote” is made available to the voters. In a vibrant democracy like India, right to express displeasure is equally important and fundamental to the essence of democracy. The same is also recognized under Section 79(d) of the 1951 Act. Therefore as a consequence of the 2013 judgment, the candidates who have filed their nominations are not contesting only among themselves, but are also essentially contesting with a “fictional candidate” in the form of NOTA. In fact, the 2013 judgment has made the right to vote for NOTA more composite by holding that not allowing a person to cast negative vote defeats the right to liberty ensured under Article 21.

It is of considerable importance that the PIL was presented only in response to the decision of the ECI not to hold elections in the parliamentary constituency of Surat. Notably, if the High Court had issued writ of mandamus to the ECI directing it to hold polls in the parliamentary constituency of Surat by making the button of the sole remaining candidate and NOTA available on the EVMs, it would have virtually affected the Certificate of Election given by the ECI to the candidate. Though the consequential impact on the election of the candidate who has been declared as “being elected unopposed” can be called into question only by way of an Election Petition, it is the rights of the voters at large which is affected. In the race between the two, fundamental rights under Articles 19 and 21 deserve primacy.

Needless to mention that as per the current legal landscape, NOTA is merely a fictional candidate with no implication at all. However, even in this scenario, the voters cannot be denied their positive right to “caste a negative vote”. Even if there might be only one voter who votes for it, its significance cannot be undermined. The sanctity of the voters’ right to have the option to vote for NOTA is a natural corollary of the Supreme Court’s 2013 landmark judgment in PUCL vs. Union of India.

The Gujarat High Court could have struck a wafer-thin balance between the statutory remedy available in the form of an Election Petition and the constitutional remedy available in the form of a PIL. The former can, at its last, only invalidate the election of a certain candidate; while the latter would have ensured the citizens in general and the voters of Surat parliamentary constituency in particular the freedom to exercise their fundamental right under Articles 19(1)(a) and 21. The apparent disinclination of the High Court underlooked the sanctity of the latter in the overwhelming argument of the former. The High Court could have come to the rescue of the rights of the voters by directing the ECI to hold elections by giving the option of the sole remaining candidate along with NOTA on the EVM.

- Advocate Sagar Sarda practices at Gujarat High Court.

In today’s innovation-driven economy, a strong intellectual property portfolio can determine wheth

Read More

As Bollywood debates fixed working hours, the industry stands at a crossroads between protecting peo

Read More

Why India’s New Data Protection Law Restores Personal Sovereignty

Read More