Pune Porsche Case: What Law Says

In Pune, a high-speed crash involving a Porsche driven by a 17-year-old resulted in the deaths of two techies, igniting debate over juvenile justice and the application of adult charges

26-06-2024In Pune, a high-speed crash involving a Porsche driven by a 17-year-old resulted in the deaths of two techies, igniting debate over juvenile justice and the application of adult charges

26-06-2024What is the story

In Pune's Yerwada area, a speeding Porsche, allegedly driven by a 17-year-old boy, killed two young techies in a motorcycle crash early Sunday. The driver, found to be drunk and speeding at over 160 kmph, was granted bail by the Juvenile Justice Board, sparking outrage. Victims' families, police, and politicians demand he be tried as an adult. The boy's father, Vishal Agarwal, a prominent builder, was arrested for neglect and providing alcohol to a minor. Agarwal allegedly allowed his unlicensed son to drive the unregistered car, avoiding road tax payments.

When does the child gets treated as an adult

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Amendment Bill, 2021, amending the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, was passed in the Rajya Sabha on July 28, 2021. Under Section 15 of the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB) assesses whether a juvenile can be tried as an adult. Crimes are categorized into three types: petty offences, serious offences, and heinous offences. According to the 2015 Act, juveniles aged 16 to 18 years charged with heinous crimes can be tried as adults. For a Child in Conflict with Law (CCL) to be tried as an adult, the age on the date of the offence determines if the accused was an adult or a child.

Section 15 stipulates that when a child allegedly commits a heinous crime, the JJB must conduct a preliminary assessment. This assessment evaluates the child's mental and physical capacity to commit the offence, their ability to understand the consequences, and the circumstances under which the crime was allegedly committed. If the Board concludes from this preliminary assessment that the child should be tried as an adult, Section 18(3) mandates that the case be transferred to the Children’s Court with the jurisdiction to try such offences. This process ensures that the decision to try a juvenile as an adult is thoroughly considered, based on specific criteria and the child's capacity to comprehend their actions.

What are the different Crimes and their Punishment

Heinous offences, such as sexual and violent sexual crimes, carry a maximum punishment of seven years or more. The 2021 amendments stipulate that for a juvenile to be tried as an adult for a heinous crime, the crime must have both a maximum and minimum sentence of seven years. This provision aims to protect children from the adult justice system. Juveniles can also be tried under laws like the NDPS Act, Arms Act, UAPA, SC/ST Act, TADA, MCOCA, and Food Safety and Standards Act. Serious offences include possession and sale of illegal substances, such as drugs and alcohol, with a maximum punishment of seven years but no prescribed minimum or a minimum of less than seven years..

Changes brought in this act

The gang-rape and murder of a 23-year-old woman in a Delhi bus in December 2012 sparked nationwide protests when one of the six accused was let off as a minor. This led the Ministry of Women and Child Development to propose stricter laws for juvenile offenders, despite opposition from child rights activists. The JS Verma Committee advised against lowering the juvenile age from 18 to 16. The 2015 amendment followed. All six accused were convicted; four were executed in March 2020, one died in jail, and the juvenile convict was released in 2015 after three years in a reform facility.

The law of bail and the Children in conflict with this law

When the minor was first presented before the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB), Section 12 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 (JJ Act) offered three options, regardless of whether the offence was bailable or non-bailable:

1. Release him on bail with or without surety

2. Release him under the supervision of a probation officer

3. Release him under the care of a fit person

Bail could be denied under three conditions: if there were reasonable grounds to believe that the release might associate the minor with known criminals, expose him to moral, physical, or psychological danger, or defeat the ends of justice. This framework shows that the law primarily aims to avoid incarcerating the Child in Conflict with Law (CiCL). The JJ Act intentionally uses the term 'child' instead of 'juvenile' to adhere to the principle of ‘non-stigmatizing semantics.’ This reflects the Act's focus on rehabilitation and protection rather than punishment.

The 300-word essay

The Juvenile Justice Act (JJ Act) underscores rehabilitation and reintegration for children in conflict with the law, prioritizing these over punitive measures, in contrast to the adult criminal justice system. This approach aims to uphold due process, ensuring accused minors receive fair trials with legal representation and evidence-based determinations of guilt.

Recent controversies highlight challenges within the system, where minors facing allegations may prematurely encounter punitive actions such as community service or reflective tasks like writing essays on road accidents and working with the Regional Transport Office (RTO) to understand traffic rules. These measures, while potentially intended to foster reflection, can raise concerns about the presumption of innocence and the need for rigorous evidentiary scrutiny before imposing such conditions.

The principle of rehabilitation under the JJ Act must harmonize with due process, essential for maintaining legal integrity and justice. Efforts to reform the system should align with these principles, ensuring fairness for minors while addressing the consequences of their actions. Striking a balance between rehabilitation and procedural rigor is critical in upholding the rule of law and protecting the rights of children in conflict with it.

Juvenile Justice Boards (JJBs), distinct from adult courts, include a Principal Magistrate and social worker members tasked with advocating a child rights perspective. However, a recent controversy over an ill-considered bail order has underscored systemic gaps in training and coordination among JJB members nationwide. The Supreme Court has previously critiqued the ad hoc nature of training for these roles, highlighting the need for structured programs to enhance skills and knowledge among JJB members.

Criticism has centered on the JJB member responsible for the contentious bail conditions, suggesting lapses in training and decision-making among social worker members and judicial officers. A more reasoned bail order, grounded in legal provisions and imposing suitable supervisory terms, could have mitigated public outcry and aligned more closely with due process.

It's essential for stakeholders advocating for victims' justice to understand that a bail order is interim and not a final judgment. The process remains incomplete pending thorough examination of evidence, the minor's background, and the circumstances of the incident.

Addressing these training deficiencies and ensuring consistent application of juvenile justice principles across JJBs are crucial for fairness and efficacy within the system. This incident underscores the urgency of structured training initiatives to empower JJB members to make informed, just decisions in accordance with the Juvenile Justice Act's spirit and uphold standards of fairness and justice.

Judicial Interpretation of Section-12

In the case of Naisul Khatun vs. State of Assam and Ors. (2010), the Gauhati High Court analyzed the criteria for granting bail to juveniles under Section 12 of the Juvenile Justice Act, noting its protective rather than punitive intent. The court emphasized that bail should be granted unless there are compelling reasons to believe it would endanger the juvenile or defeat the ends of justice. This approach reflects a legislative aim to safeguard juveniles in conflict with the law.

Similarly, the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, in "X" Juvenile vs. Union Territory of J&K (2024), interpreted the "ends of justice" provision, asserting that it must prioritize the welfare of the juvenile. This underscores the Act's objective of rehabilitation and protection over retribution.

Addressing the applicability of the Criminal Procedure Code's bail provisions to minors, the High Court of Chhattisgarh in Tejram Nagrachi Juvenile vs. State of Chhattisgarh and Ors. (2019) clarified that bail for juveniles should be determined exclusively under Section 12 of the Juvenile Justice Act, excluding Sections 437 and 439 of the Code. This reinforces the special considerations and protections afforded to juveniles under the Act.

Contrary to public sentiment to penalize severe crimes, an objective review of legal principles and case law supports the Juvenile Justice Board's decision to grant bail in this instance. The Board's decision aligns with established precedents and the underlying principles of the Juvenile Justice Act, which prioritize the welfare and rehabilitation of juveniles in conflict with the law while ensuring that bail decisions are made with utmost caution and consideration of the juvenile's best interests.

Litigation Before Adjudication-A Long Due Legal Mandate

Read More

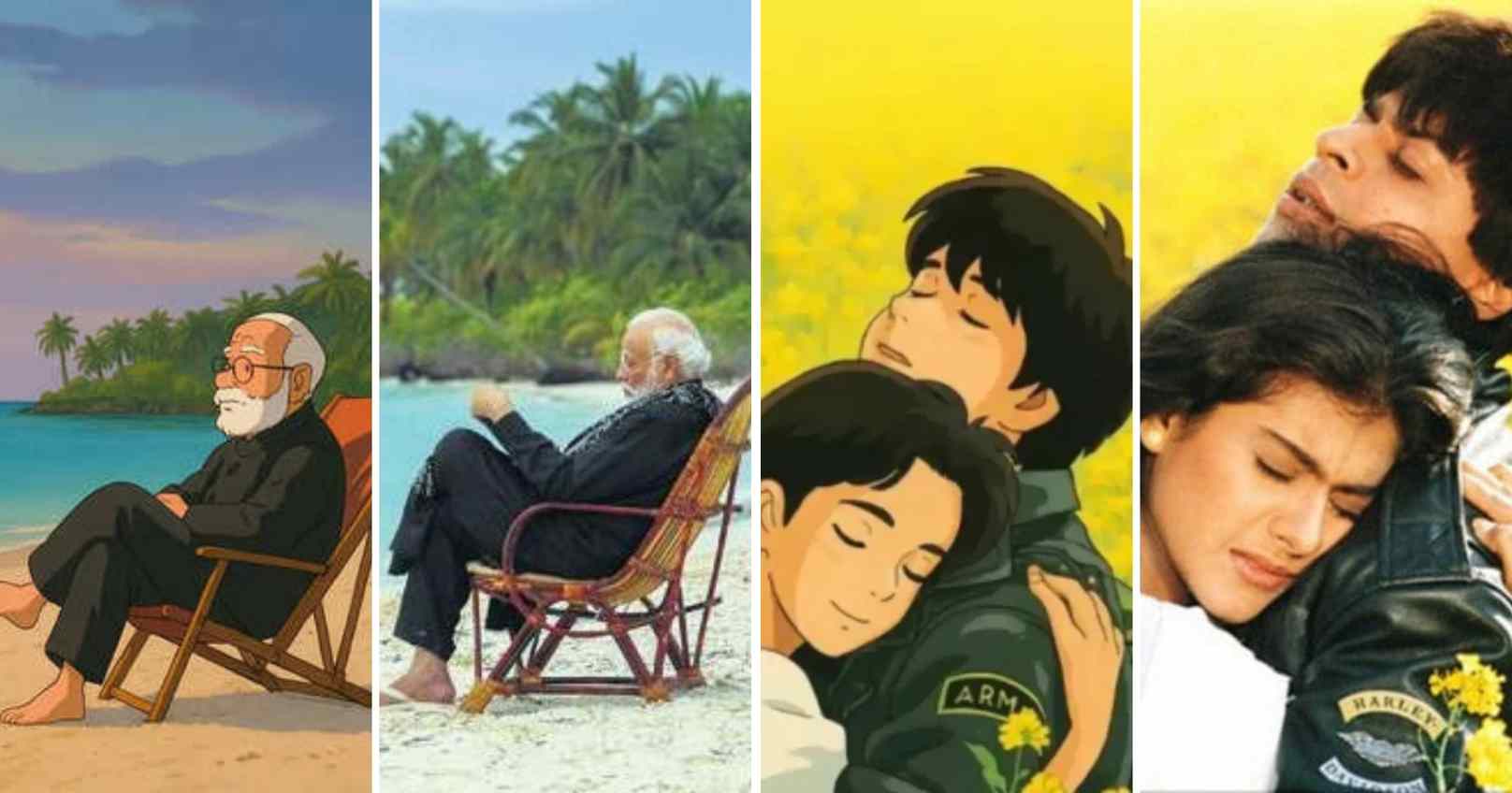

As AI-generated art gains popularity, especially through tools that mimic Studio Ghibli’s iconic s

Read More

India’s fintech Self-Regulatory Organisations (SROs) are being reimagined as key policy influencer

Read More