Reservation policies in India, enshrined in the Constitution, represent a progressive legal measure aimed at the upliftment of marginalized sections of society, specifically the Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs). These provisions are rooted in Articles 15(4), 16(4), and 46 of the Indian Constitution, which empower the State to make special provisions for the advancement of socially and educationally backward classes. The rationale behind such reservations is to rectify historical injustices and systemic discrimination that have impeded the socio-economic progress of these groups. By facilitating access to education, employment, and political representation, reservations serve as a catalyst for social mobility and integration.

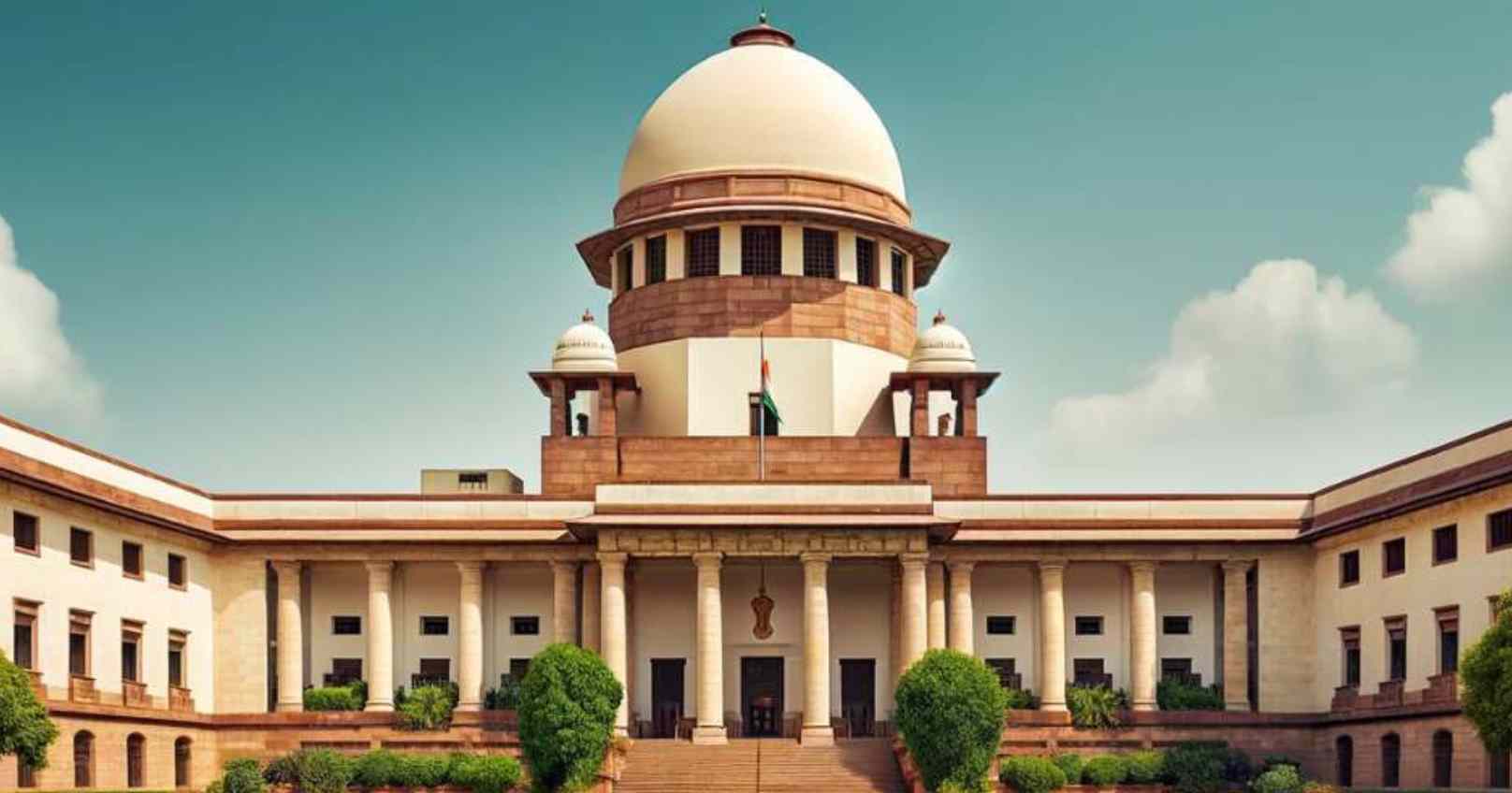

The recent Supreme Court ruling endorsing the sub-classification of Scheduled Castes for separate quotas for the most backward groups within these categories underscores the dynamic nature of affirmative action policies. This judgment recognizes the varying degrees of disadvantage within the SCs and aims to ensure that the benefits of reservation reach the most marginalized. By allowing for sub-classification, the judiciary has affirmed the necessity of nuanced approaches to social justice, thereby reinforcing the constitutional mandate of equality and non-discrimination.

Constitutional Provisions:

The Indian Constitution enshrines several provisions to ensure equality and upliftment of marginalized sections of society. Article 14 mandates that the State shall not deny any person equality before the law or equal protection of the laws within the territory of India. Complementing this, Article 15(1) prohibits the State from discriminating against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth, or any of them. Importantly, Article 15(4) allows the State to make special provisions for the advancement of socially and educationally backward classes of citizens, including Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

Article 16 further elaborates on equality of opportunity in public employment. Clause (1) guarantees equality of opportunity for all citizens in matters of state employment or appointment. Clause (2) prohibits discrimination on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, or residence. Crucially, Clause (4) empowers the State to reserve appointments or posts for any backward class of citizens that is, in the opinion of the State, not adequately represented in state services.

The term 'Scheduled Castes' is defined in Article 366(24) as castes, tribes, or parts thereof, as deemed under Article 341. Article 341(1) grants the President the authority to notify such groups as Scheduled Castes, in consultation with the Governor of the respective state. Article 341(2) allows Parliament to modify this list, ensuring that any changes to the notification issued under Article 341(1) are made by law.

Additionally, Articles 342 and 342-A provide similar provisions for the notification of Scheduled Tribes and socially and educationally backward classes, respectively. These provisions collectively reinforce the State's commitment to ensuring social justice and equality by enabling affirmative action and reservation policies aimed at the upliftment of marginalized communities in India.

Background of Present Reference Case:

In the realm of affirmative action in India, several state legislatures have enacted laws to provide reservations for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Backward Classes (BCs), each facing legal scrutiny. The Punjab Scheduled Castes and Backward Classes (Reservation in Services) Act, 2006, mandates 25% reservation for SCs and 12% for BCs in direct recruitment. Section 4(5) reserves 50% of SC vacancies for specific subgroups, but was deemed unconstitutional by the Punjab and Haryana High Court in 2010, referencing EV Chinniah v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2005) 1 SCC 394. Subsequently, a Three-Judge Bench referred the matter for review considering Articles 16, 338, and 341, questioning the applicability of Chinniah to the broader constitutional framework set by Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992) Supp (3) SCC 217.

Similarly, the Government of Haryana's 1994 notification classified SCs into Blocks A and B, allocating quotas accordingly. The Punjab and Haryana High Court invalidated this classification in 2006, citing Chinniah, leading to a Supreme Court challenge, tagged with the Punjab Act appeals.

Conversely, Tamil Nadu enacted the Tamil Nadu Arunthathiyars Act, 2009, reserving 16% of SC educational and employment quotas for Arunthathiyars, a subgroup within SCs. This law was challenged in the Supreme Court under Article 32, contending it contradicts Chinniah. These challenges were consolidated with the Present case.

In EV Chinnaiah, the bench comprising Justices N. Santosh Hegde, S. N. Variava, B. P. Singh, H. K. Sema, and S. B. Sinha concluded that the castes listed in the Presidential Order under Article 341(1) of the Constitution constitute a single, homogeneous group and cannot be further subdivided. Article 341(1) authorizes the President of India to officially recognize certain groups as Scheduled Castes in any State or Union Territory, a process conducted in consultation with the Governor and subsequently publicly notified. This designation may encompass castes, races, tribes, or their sub-groups.

On 27 August 2020, in the case of State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh, a Constitution Bench determined that the judgment in Chinnaiah necessitates reconsideration by a larger Bench of seven Judges, as it overlooked several critical aspects relevant to the issue.

Rationale Behind Referring the Case to a Larger Bench:

In Indra Sawhney, the Court affirmed that it is constitutionally permissible to classify the backward classes into 'backward' and 'more backward' categories. This principle applies equally to Articles 341, 342, and 342A, necessitating an examination of whether sub-classification within Scheduled Castes is inconsistent with this precedent. The Court interpreted the term "Backward Classes" in Article 16(4) to encompass both socially and educationally backward classes as well as Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

The judgment highlighted that Scheduled Castes are not a homogeneous group, and preferential treatment can be extended to the most disadvantaged segments to enhance equal opportunity and achieve the aims of reservation. Under Article 16(4), the State may rationally allocate reservation benefits to specific castes within the Scheduled Castes if they are underrepresented, without altering the list of Scheduled Castes as per Article 341. The Court emphasized that preferential treatment for certain castes does not exclude others from receiving reservation benefits, as affirmed in Jarnail Singh v. Lachhmi Narain Gupta (2018) 10 SCC 396 which held that excluding the "creamy layer" from reservation benefits does not affect the Presidential List under Article 341. Thus, sub-classification within the Scheduled Castes can be implemented without disrupting the overall framework of reservations.

Issues Framed by the Bench:

The Constitution Bench is tasked with determining the validity of sub-classification within Scheduled Castes for affirmative action, including reservation. The issues for consideration are as follows:

Permissibility of Sub-Classification: Whether the sub-classification of a reserved class is permissible under Articles 14, 15, and 16 of the Constitution, which guarantee equality before the law and equal protection of the laws, and provide for special provisions for backward classes?

Nature of Scheduled Castes: Whether the Scheduled Castes should be regarded as a homogeneous or heterogeneous group, impacting the rationale for and application of sub-classification?

Homogeneity Under Article 341: Whether Article 341 creates a homogeneous class of Scheduled Castes through the operation of its deeming fiction, which designates certain castes as Scheduled Castes for constitutional purposes?

Limits on Sub-Classification: Whether there are any constitutional limits or constraints on the scope and application of sub-classification within the Scheduled Castes, ensuring it aligns with the principles of justice and equality?

Judgement:

Article 14 of the Constitution permitted the sub-classification of a class when it was not uniformly situated for the purposes of law. In examining the validity of sub-classification, the Court had to determine if the class was a homogeneous and integrated group for fulfilling the objectives of such classification. If the class was not integrated for the intended purpose, sub-classification could be permissible provided it met the two-prong intelligible differentia standard. This standard required that the sub-classification be based on clear and rational criteria that differentiated between the sub-classes in a manner relevant to the objective of the classification.

Article 341(1) did not establish a deeming fiction but utilized the term “deemed” to signify that castes or groups notified by the President were to be "regarded as" Scheduled Castes. The provision did not create a homogeneous class but ensured that the castes included in the list were entitled to the benefits afforded to Scheduled Castes under the Constitution. The logical consequence of this provision was the entitlement to benefits rather than the formation of an integrated, homogeneous class. The Court held that sub-classification within the Scheduled Castes did not contravene Article 341(2). This Article did not preclude the possibility of sub-classification but ensured that such sub-classification did not result in preference or exclusive benefits being granted to certain castes or groups over all reserved seats within the Scheduled Castes category. Sub-classification was permissible as long as it did not violate the principle of equal distribution of reserved benefits among all castes listed under Article 341.

Dissenting Opinion:

In her dissent, Justice Trivedi opined that the Presidential list of Scheduled Castes, as notified under Article 341, cannot be modified by the States. The inclusion or exclusion of castes from this list is solely within the jurisdiction of Parliament through legislative action. Any attempt at sub-classification would constitute an unauthorized alteration of the Presidential list. The intent of Article 341 was to prevent political influences from affecting the SC-ST list.

Justice Trivedi emphasized the importance of adhering to a plain and literal interpretation of the Constitution. She asserted that preferential treatment for any sub-class within the Presidential list could result in the deprivation of benefits for other castes within the same category. In the absence of specific executive or legislative authority, States lack the competence to effectuate sub-classification of castes and to allocate reserved benefits in a manner that would affect all Scheduled Castes. Permitting such sub-classification by the States would amount to a misuse of power.

Conclusion & Way Forward:

The Supreme Court's endorsement of sub-classification within the Scheduled Castes marks a pivotal shift in affirmative action, acknowledging the diverse socio-economic challenges faced by different sub-groups within this category. This judgment affirms the need for nuanced reservation policies to address varying levels of disadvantage and ensures that the benefits of affirmative action are equitably distributed. By allowing states to implement sub-classification, the Court has set a precedent for more targeted and effective affirmative action, potentially improving representation for the most marginalized groups. However, careful implementation is crucial to avoid any potential exclusion or deprivation of benefits for other Scheduled Castes. States will now need to balance targeted reservations with principles of fairness and equal opportunity, ensuring that the implementation of this judgment promotes both equity and justice.

- The Author is a Law Graduate from HPNLU, Shimla.