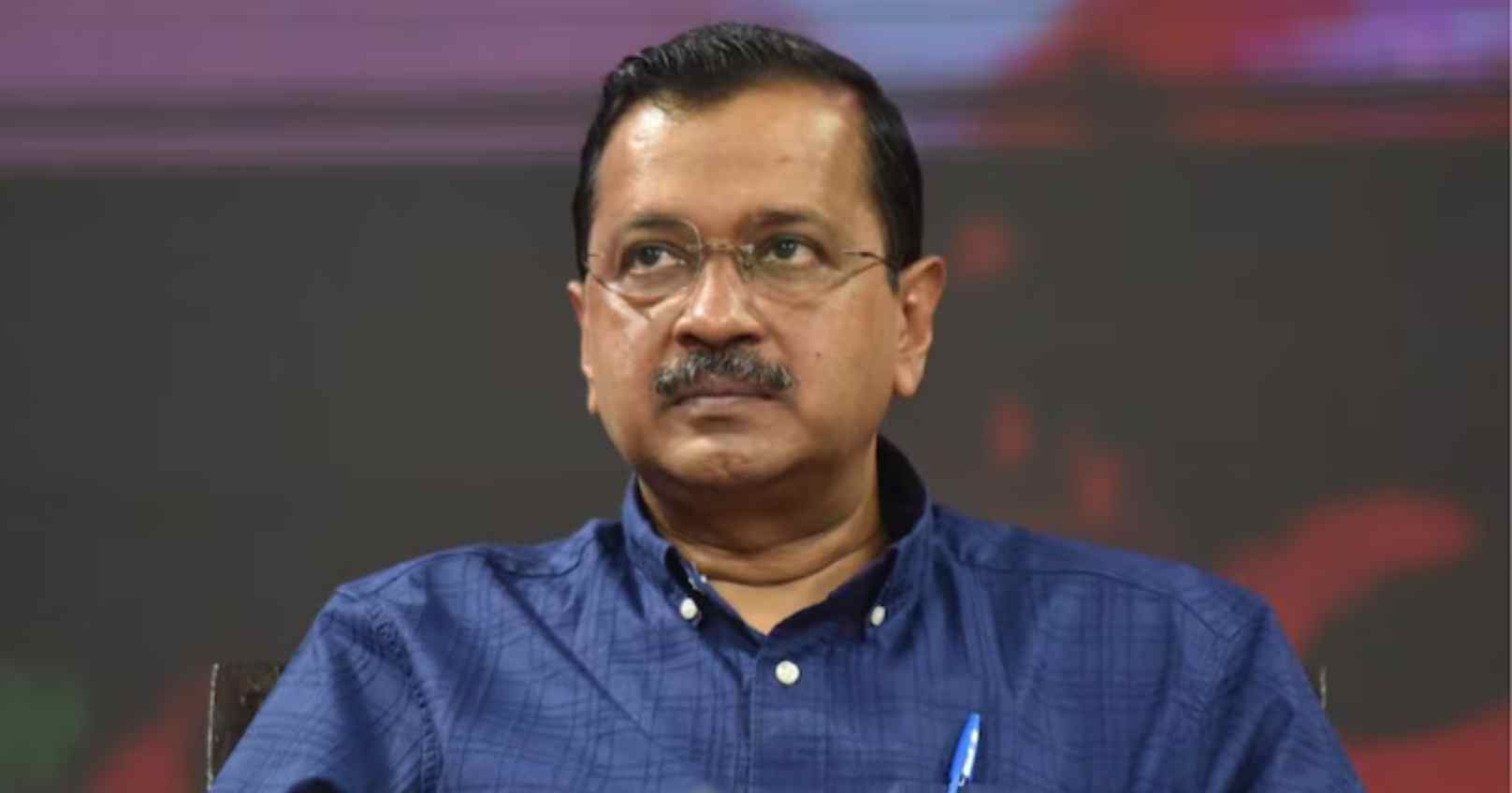

The Supreme Court's decision to grant bail to Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, despite upholding the legality of his arrest in connection with the Delhi liquor policy case, has raised significant questions about the balance between legal procedure and the protection of personal liberty under the Indian Constitution. The case, involving allegations of corruption and money laundering under the Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA) and the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), has highlighted important legal principles related to arrest, detention, and the right to bail.

In this article, we will analyze the Supreme Court's ruling through a discussion of the separate judgments delivered by Justices Surya Kant and Ujjal Bhuyan, focusing on the legality of the arrest, the timing of the CBI’s actions, and the implications for personal liberty enshrined under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution.

Background of the Case

Arvind Kejriwal, the Chief Minister of Delhi and leader of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), was arrested by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) on June 26, 2024, in connection with a corruption case stemming from allegations regarding the Delhi liquor policy. His arrest came after a prolonged period of investigation, during which the Enforcement Directorate (ED) had already taken Kejriwal into custody on March 21, 2024, in connection with a money laundering case related to the same liquor policy scandal. The arrest by the CBI occurred after Kejriwal was granted bail in the ED case by a special judge, which was later stayed by the High Court.

The case had been closely followed due to the involvement of several political figures, including co-accused Manish Sisodia, K Kavitha, Vijay Nair, and Sanjay Singh, all of whom were also granted bail in connection with the case. Kejriwal's bail petition was initially dismissed by the Delhi High Court on August 5, 2024, before being taken up by the Supreme Court.

Timeline of the Case

1. The CBI registered a FIR bearing FIR No. RC0032022A0053 on 17.08.2022 under Sections 120B read with Section 477A of the Indian Penal Code, 1806 (hereinafter ‘IPC’) and Section 7 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 but it did not bear Kejriwal’s name.

2. On 21.03.2024, the Directorate of Enforcement (hereinafter ‘ED’) arrested the Kejriwal in the purported exercise of its power under Section 19 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002.

3. The apex court granted Kejriwal interim bail on 10.05.2024, until 01.06.2024.

4. The Special Judge vide order dated 20.06.2024 granted the Kejriwal regular bail while his bail in the ED matter was pending before this Court and reserved for judgement. However, the ED swiftly sought the cancellation of that bail order. The High Court on 21.06.2024 stayed the operation of that order, as a result of which, the Kejriwal continued to remain in jail.

5. CBI moved an application on 24.06.2024 before the Special Judge (PC Act) (hereinafter ‘Trial Court’) under Section 41A of the CrPC, seeking to interrogate the Kejriwal, which was thereupon allowed.

6. Having completed interrogation and examination, the CBI filed an application on 25.06.2024 seeking permission to arrest the Kejriwal and for the issuance of production warrants.

7. Thereafter, the Trial Court allowed the CBI’s application noting that the accused was already in judicial custody in the ED matter.

8. In the meantime, the High Court conclusively stayed the order granting regular bail to the Kejriwal in the ED matter on 25.06.2024 itself.

9. On 29.06.2024, the Trial Court remanded the Kejriwal to judicial custody till 12.07.2024.

10. On 02.07.2024, when the Petition was heard, the High Court issued notice to the CBI and scheduled the matter to be heard on 17.07.2024.

11. In the interregnum, the Kejriwal also approached the High Court under Section 439 CrPC, seeking regular bail in connection with the subject FIR.

12. On 05.07.2024, when the Bail Application came up for hearing, the High Court issued notice and renotified it to be heard on 17.07.2024, along with the Writ Petition challenging the very arrest of the Kejriwal.

13. The High Court heard the case on 17.07.2024, reserved judgment, and renotified the Bail Application for 29.07.2024. On 05.08.2024, it upheld the CBI's arrest and denied regular bail, allowing the Kejriwal to seek relief from the Trial Court.

14. The High Court denied the Kejriwal's request for regular bail, citing the need for a deeper assessment of his role in the alleged conspiracy and directing him to approach the Sessions Court since the chargesheet had been filed after the Bail Application.

15. On 12.07.2024, this Court granted the Kejriwal interim bail in the ED case, but he remains in custody due to the ongoing CBI proceedings.

The Supreme Court’s Verdict: Two Perspectives

The judgment delivered by the Supreme Court on the petitions filed by Arvind Kejriwal reflects differing judicial views on the nature and timing of his arrest, while ultimately reaching a consensus on the issue of bail. The bench comprised Justices Surya Kant and Ujjal Bhuyan, who delivered separate but intersecting opinions.

1. Justice Surya Kant: Legality of the Arrest

Justice Surya Kant’s opinion centered on the legality of the arrest, holding that the procedure followed by the CBI complied with all necessary legal requirements. He emphasized that the arrest did not violate the mandate of Sections 41 and 41A which govern arrests made without a warrant. According to him, there were no procedural irregularities, and Kejriwal's arrest was justified within the confines of the law. There is no impediment in terms of arresting a person already in custody for the purposes of investigation, whether for the same offence or for an altogether different offence.

However, Justice Kant highlighted that while the arrest itself was lawful, Kejriwal's continued incarceration posed a threat to his personal liberty, particularly given that the chargesheet had already been filed and the trial was unlikely to conclude anytime soon. He noted that prolonged detention without trial would infringe upon Kejriwal's right to personal liberty under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. Citing the bail granted to Kejriwal in the ED case, as well as to several co-accused in both the CBI and ED matters, Justice Kant argued that bail should be granted to Kejriwal to uphold the constitutional right to liberty.

2. Justice Ujjal Bhuyan: Questioning the CBI’s Intentions

In contrast, Justice Ujjal Bhuyan's opinion raised significant questions about the necessity and timing of the CBI’s actions in arresting Kejriwal. Justice Bhuyan expressed skepticism regarding the agency's decision to arrest Kejriwal 22 months after registering the case, especially when the CBI had not felt it necessary to arrest him during this period despite having interrogated him in 2023.

In Joginder Kumar Vs. State of U.P., a three Judge bench of this Court examined the interplay of investigation and arrest. In the case of Sidhartha Vashisht alias Manu Sharma Vs. State (NCT of Delhi), this Court emphasized that investigation must be fair and effective.

According to Justice Bhuyan, the timing of the arrest appeared to be in response to Kejriwal’s bail in the ED case, raising concerns about whether the CBI's move was intended to frustrate the court’s decision in the ED matter. He suggested that such an arrest, coming immediately after the ED bail, undermined the principles of justice and fairness. Justice Bhuyan's observations highlighted the importance of avoiding perceptions of bias and unfairness in criminal investigations, particularly when the investigating agency is as high-profile as the CBI. While referring to the case of Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar, This Court in the case of he observed that arrest brings humiliation, curtails freedom and cast scars forever. Again in the case of Mohd. Zubair Vs. State (NCT of Delhi), a threeJudge Bench of this Court once again emphasized that the existence of the power of arrest must be distinguished from the exercise of the power of arrest. Referring to its earlier decision in Arnab Ranjan Goswami Vs. Union of India, this Court observed that the courts should be alive to both ends of the spectrum: the need to ensure proper enforcement of criminal law on the one hand and the need to ensure that the law does not become a ruse for targeted harassment on the other hand.

Justice Bhuyan further pointed out that the continued detention of Kejriwal in the CBI case was unwarranted, given that he had already secured bail in the more stringent PMLA case. He termed the arrest by the CBI as a "travesty of justice" and concluded that there was no justification for keeping Kejriwal in custody in the predicate offence under the PCA when he had already been granted bail in the ED case.

Article 21 and the Right to Personal Liberty

A key theme in both judgments was the emphasis on the constitutional right to personal liberty under Article 21, which protects individuals from arbitrary arrest and prolonged detention. Both Justices Kant and Bhuyan agreed that despite the legality of Kejriwal's arrest, his continued incarceration would violate the principles enshrined in Article 21. This resonates with the broader judicial philosophy that bail, not jail, should be the norm, especially when the accused has already been in custody for a considerable period, and the trial is unlikely to conclude in the near future.

The evolution of bail jurisprudence in India underscores that the ‘issue of bail is one of liberty, justice, public safety and burden of the public treasury, all of which insist that a developed jurisprudence of bail is integral to a socially sensitised judicial process’.

This Court in Union of India v. K.A. Najeeb has expanded this principle even in a case under the provisions of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (hereinafter ‘UAPA’) notwithstanding the statutory embargo contained in Section 43-D(5) of that Act, laying down that the legislative policy against the grant of bail will melt down where there is no likelihood of trial being completed within a reasonable time.

The Supreme Court’s decision to grant bail to Kejriwal reflects a balancing act between upholding the procedural legality of an arrest and safeguarding personal liberty. The case serves as a reminder that, in the Indian legal system, the right to liberty is paramount, and courts must be vigilant in ensuring that individuals are not unjustly deprived of their freedom.

Implications for Investigative Agencies

Justice Bhuyan's observations on the CBI's conduct are of particular relevance to the functioning of investigative agencies in India. He reiterated that the CBI, as a premier investigative agency, must not only act fairly but must also be perceived to be acting impartially. His reference to the infamous "caged parrot" comment made by the Supreme Court in earlier cases underscores the need for the CBI to maintain its independence and credibility.

The perception that investigative actions, such as arrests, are being used as tools to counter judicial decisions (as Justice Bhuyan suggested in this case) can undermine public trust in law enforcement institutions. The integrity of the criminal justice system depends on the transparency and impartiality of investigative agencies, especially in cases involving political figures.

Conditions Imposed on Bail

While granting bail, the Court imposed certain conditions on Kejriwal’s movement and functions as Chief Minister, similar to those imposed during his interim bail in the ED case. These conditions restrict him from visiting the Chief Minister’s office or the Delhi Secretariat, except when clearance from the Lieutenant Governor is required. While Justice Bhuyan expressed reservations about these conditions, he chose not to interfere due to judicial discipline.

These restrictions raise questions about the extent to which a sitting Chief Minister can be effectively barred from discharging his official duties. The imposition of such conditions in high-profile political cases may have significant implications for governance, especially when the accused continues to hold public office.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision in Arvind Kejriwal's case underscores the complex interplay between the legal validity of an arrest, the right to personal liberty, and the broader implications for the functioning of investigative agencies in India. While the Court upheld the legality of the arrest, it also highlighted the importance of ensuring that the right to liberty is not unduly compromised by prolonged detention. The case serves as a reminder of the judiciary’s role as a guardian of constitutional rights, even as it navigates the challenges of high-profile political cases.

- Varun K. Chopra is an advocate at the Supreme Court of India.